- Sat. Apr 20th, 2024

Latest Post

From Bag Maker to Brick-and-Mortar: Tulsa’s Empowered Female Business Owners

Lori Nair, a female business owner in Tulsa, started her shop by chance 22 years ago when her daughter needed a special bag for her wheelchair. She began sewing and…

Iranian Missiles on Tehran Billboard Spark Concerns Amid Growing Tensions in Region; Greece Faces its Own Demographic, Climate Change, and Investment Gap Challenges.

A billboard with a picture of Iranian missiles has been spotted on a street in Tehran, Iran, sparking concerns about the growing tensions in the region. Meanwhile, Greece is facing…

World Heritage Sites under Fire: UN implicated in violent eviction of Indigenous people

A new report has implicated the United Nations (UN) in the violent eviction of Indigenous people from six World Heritage Sites in Africa and Asia. These sites, often ancestral lands…

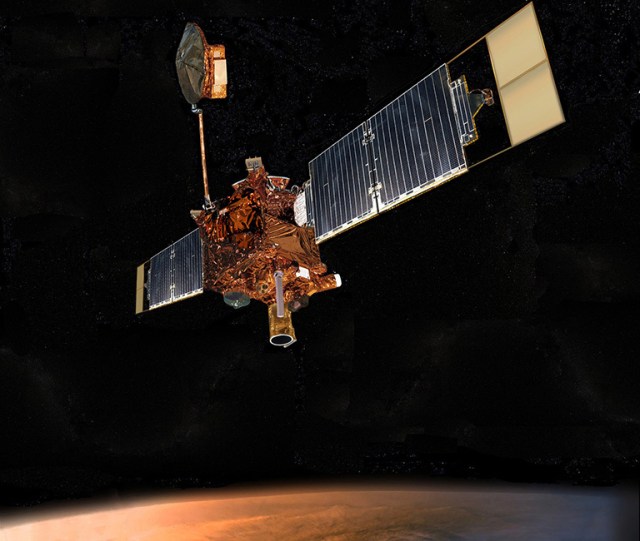

Decade-Long Discoveries: Mars Global Surveyor’s Legacy and the Possibility of Liquid Water on the Red Planet

Mars Global Surveyor was a game-changing spacecraft that spent a decade orbiting the Red Planet, completely transforming scientists’ knowledge of Mars. With its state-of-the-art equipment and cutting-edge technology, the mission…

Poland Secures 250 Million Euros in World Bank Funding for Clean Air Initiative

Poland has recently signed a 250-million-euro agreement with the World Bank to support its Clean Air program, announced Finance Minister Andrzej Domanski. The Clean Air initiative is part of a…

Congressman Steve Cohen Celebrates $21.3 Million Federal Grant for Memphis Head Start Programs

In a statement, Congressman Steve Cohen (TN-9) announced that Memphis Health Center Inc., Porter-Leath, and the Shelby County Board of Education have been awarded grants totaling $21,309,797 from the U.S.…

Oregon Ducks Break World Record in Distance Medley Relay at Eugene Olympics

Brandon Miller, Henry Wynne, Isaiah Harris, and Brannon Kidder set a new world record in the distance medley relay at the Oregon Relays in Eugene, USA on Friday (19). The…

The Greatest Hip-Hop Beefs in Recent Years: Examining Kendrick Lamar and Drake’s Ongoing Feud and J. Cole’s Retraction of His Diss Track

In a recent guest verse on Future and Metro Boomin’s hit “Like That,” Kendrick Lamar reignited his ongoing feud with Drake, sparking what has become one of the biggest rap…

Ronnie O’Sullivan’s Quest for Consistency: Finding the Ultimate ‘Turbo Button’

In a recent interview with Eurosport’s Rachel Casey, snooker legend Ronnie O’Sullivan discussed his desire to find a “turbo button” that would allow him to consistently perform at a high…

Japanese Companies Turn to AI to Predict Employee Resignations, Create More Engaged Workforce

In an effort to retain their young employees, Japanese companies are turning to AI tools for predicting employee resignations. A new tool developed by researchers at Tokyo City University analyzes…