- Thu. Apr 25th, 2024

Latest Post

Wearable Sensors Show Promising Results in Improving Postural Ergonomics for Neurosurgeons

A pilot study published in the Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine on April 19, 2024, explored the use of wearable technology to assess postural ergonomics and provide biofeedback to neurosurgeons. The…

Finance Professionals Worldwide Optimistic about Global Economy, Despite Risks and Challenges Ahead

A recent survey by ACCA and IMA found that finance professionals worldwide are feeling more optimistic about the global economy. According to the Global Economic Conditions Survey (GECS), confidence levels…

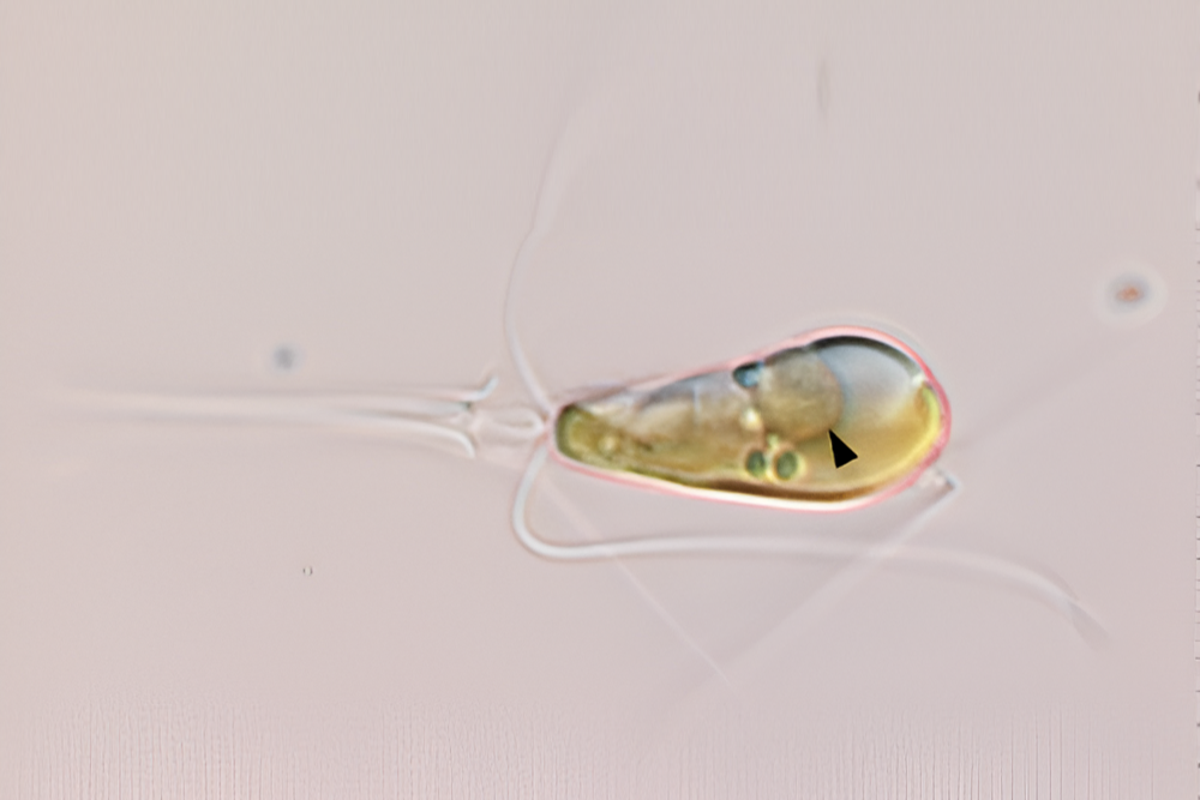

Rare Evolutionary Event: Two Lifeforms Merge to Create a Single Organism through Primary Endosymbiosis

A fascinating evolutionary event has occurred for the first time in a billion years, as two lifeforms have merged to form a single organism through primary endosymbiosis. This phenomenon has…

German Leaders Break Taboo: The Debate Over Working Hours in Germany Amid Economic Concerns

In recent months, German politicians and business leaders have started to openly discuss a topic that was once considered taboo: the idea that their fellow citizens do not work enough.…

LG Electronics Bounces Back in First Quarter with Increasing Demand for Streaming Services and Home Appliances

LG Electronics’ TV business has made a strong comeback in the first quarter, thanks to the recovery of demand in Europe and the increasing popularity of streaming services. The South…

Drones Make a Splash in Miami Township: Enhancing Community Safety and Improving Law Enforcement Capabilities

Law enforcement in Miami Township is utilizing drones to enhance community safety and improve their capabilities. Chief Mike Mills stated that the department has only been using drones for about…

From Classroom to Career: Ohio High School Tech Internship Bridges Education-Industry Gap

The High School Tech Internship program is a new initiative by the Governor’s Office of Workforce Transformation, which will provide real-life experience and on-the-job technology training to 10 high school…

New Ulm Cathedral’s Kiah Helget Hits Two-Run Home Run, Impresses with Favorites and Athletic Skills

On Monday, senior Kiah Helget hit a two-run home run for New Ulm Cathedral against Nicollet at Harman Park. The Greyhounds won the game in just four innings with a…

Black Saturday: The Kidnapping of Hirsch Goldberg-Polin by Hamas and the Analysis of the Hostage Video

On October 7th, 2023, Hirsch Goldberg-Polin, a dual citizen of Israel and the United States, was kidnapped by Hamas militants. This event became known as Black Saturday. The Kan-11 television…

Revolutionizing Retail: Unlocking the Benefits and Opportunities of RFID Technology

RFID technology is revolutionizing the retail industry, providing a range of benefits to retailers, associates, and consumers. This report, as part of our RetailTech series, explores the developments, insights, and…